House Democrats Can Help Senate Democrats Win Upcoming Reconciliation Debate

Democrats may expand the categories of people who qualify for lawful permanent resident (LPR) status by including the proposal in the Build Back Better Act (HR 5376) reconciliation bill presently working its way through the House. Reconciliation is a fast-track process, the purpose of which is to make it easier for lawmakers - especially in the Senate - to pass budget-related legislation. It does so by preventing senators from filibustering reconciliation bills on the Senate floor. Consequently, fifty Democrats and Vice President Kamala Harris can pass HR 5376 over Republican objections without securing sixty votes to invoke cloture (i.e., to end debate) on the measure first.

The Senate parliamentarian recently advised Democrats that one of the particular rules that regulate the reconciliation process - the so-called Byrd Rule – bars the Senate from expanding LPR status in HR 5376. The Byrd Rule’s purpose is to prevent senators from circumventing the filibuster by including non-budgetary provisions in reconciliation bills. The parliamentarian asserts that the Byrd Rule prohibits Democrats’ LPR expansion because its budgetary impact is “merely incidental” to its non-budgetary components.

But the Senate does not define "merely incidental" in its rules. The parliamentarian’s advice does not cite a precedent (i.e., an instance in the past when the Senate interpreted its rules in a specific parliamentary context) that demonstrates that senators have adjudicated the question of whether the LPR provision violates the test. And until senators do so, there is no precedent (or rule) to prohibit Democrats from including the LPR provision in HR 5376.

Three Steps To Make Winning Easier

Notwithstanding the parliamentarian’s advice, Democrats can increase the likelihood that Congress approves their proposed LPR expansion via the reconciliation process by taking three steps to set up the debate in the Senate.

First, the House can include the LPR provision in HR 5376 before sending the bill to the Senate. In doing so, Democrats gain an advantage over opponents of the provision by forcing them to remove it from the reconciliation bill on the Senate floor instead of requiring the provision’s supporters to add it by amending the legislation.

Second, Vice President Harris can make it harder for opponents of the LPR expansion to remove the provision from HR 5376. For example, a senator may cite the parliamentarian’s advisory opinion and raise a point of order against the LPR provision because it violates the Byrd Rule's "merely incidental" test. But the Senate’s rules and precedents stipulate explicitly that its presiding officer - the vice president - makes the initial decision whether that point of order is valid. Given that no rule or precedent suggests the LPR provision fails the "merely incidental" test, Vice President Harris can rule consistent with the rules and precedents if she decides that the Byrd Rule point of order is not valid. Harris ruling in this way makes it harder for opponents of the provision to remove it from HR 5376 by raising a point of order against it. This is because the rules require a three-fifths vote of senators duly chosen and sworn (typically sixty) to overturn the presiding officer’s ruling in this case.

Finally, Democrats can make it harder for senators to remove the LPR expansion from HR 5376 by offering an amendment to strike the provision from the House-passed reconciliation bill simply by including it at the end of the legislation instead of in its middle. The location of the provision is essential because it can make it easier for senators to force an up-or-down vote on the LPR expansion instead of a vote on what the rules say (i.e., a point of order vote) or a vote that strikes the provision implicitly (i.e., a substitute amendment vote - see below). How the provision’s location in the House-passed bill does so is highlighted by the Democrats’ failed effort earlier this year to increase the federal minimum wage via the reconciliation process.

Flawed Strategy in Minimum Wage Debate

Democrats included a provision that increased the federal minimum wage in the House-passed American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (Public Law 117-2) reconciliation bill.

The Senate parliamentarian subsequently advised senators that the provision in the House-passed bill violated the Byrd Rule’s “merely incidental” test. The parliamentarian did not, however, identify a precedent to support her interpretation of the rule.

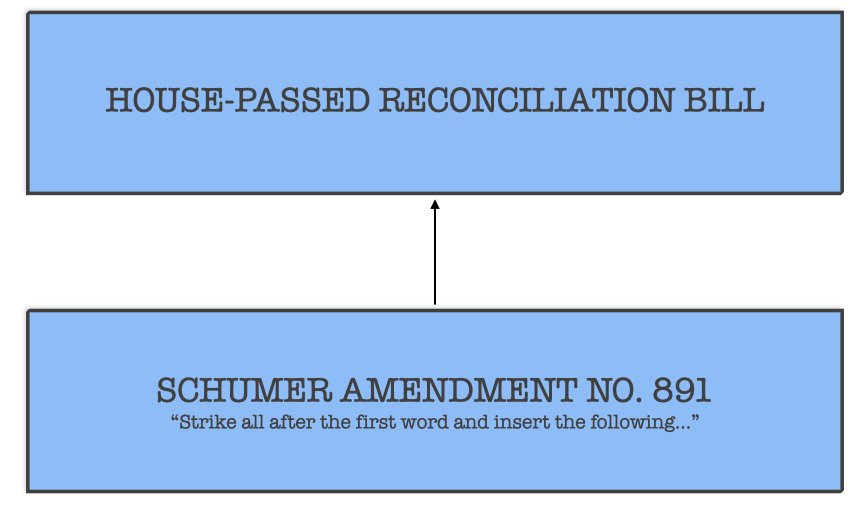

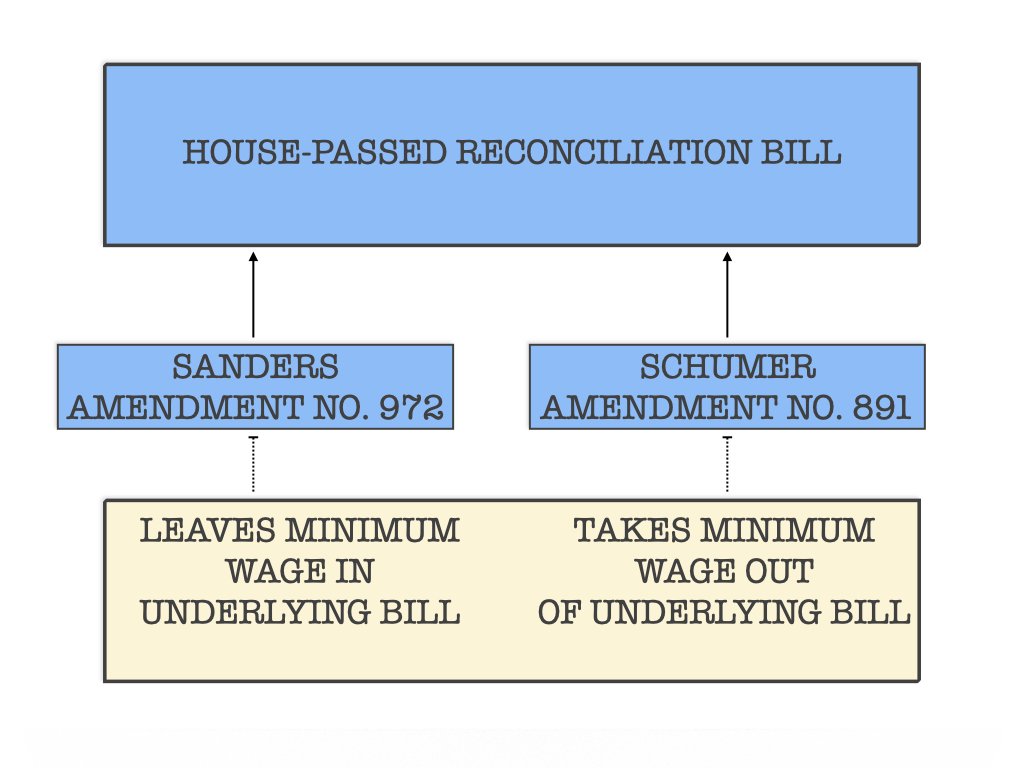

Notwithstanding the absence of a clear precedent, Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-NY, offered an amendment (Schumer Amendment No. 891) to the House-passed bill that made many substantive policy changes to the underlying legislation.

Schumer’s amendment also removed the minimum wage provision from the House-passed bill without saying so (more later).

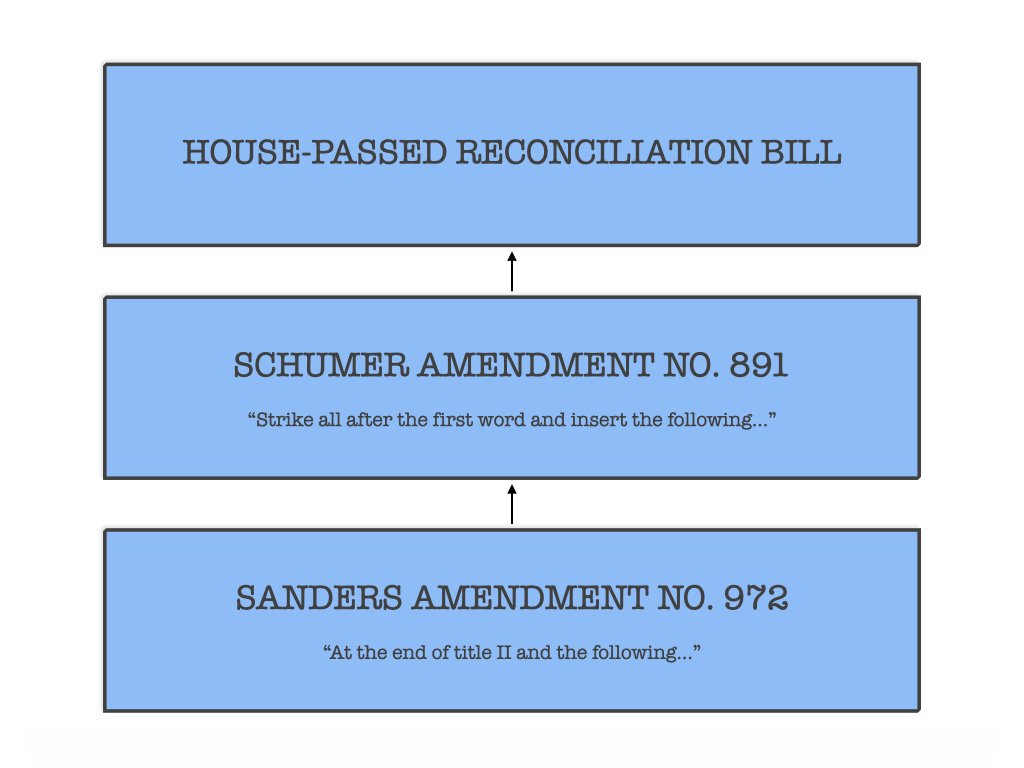

Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., next offered an amendment (Sanders Amendment No. 972) to Schumer’s amendment.

Sanders’ amendment would have added a minimum wage provision nearly identical to the one included in the underlying House-passed bill to the Schumer amendment (which, among other things, removed the minimum wage provision from the House-passed bill).

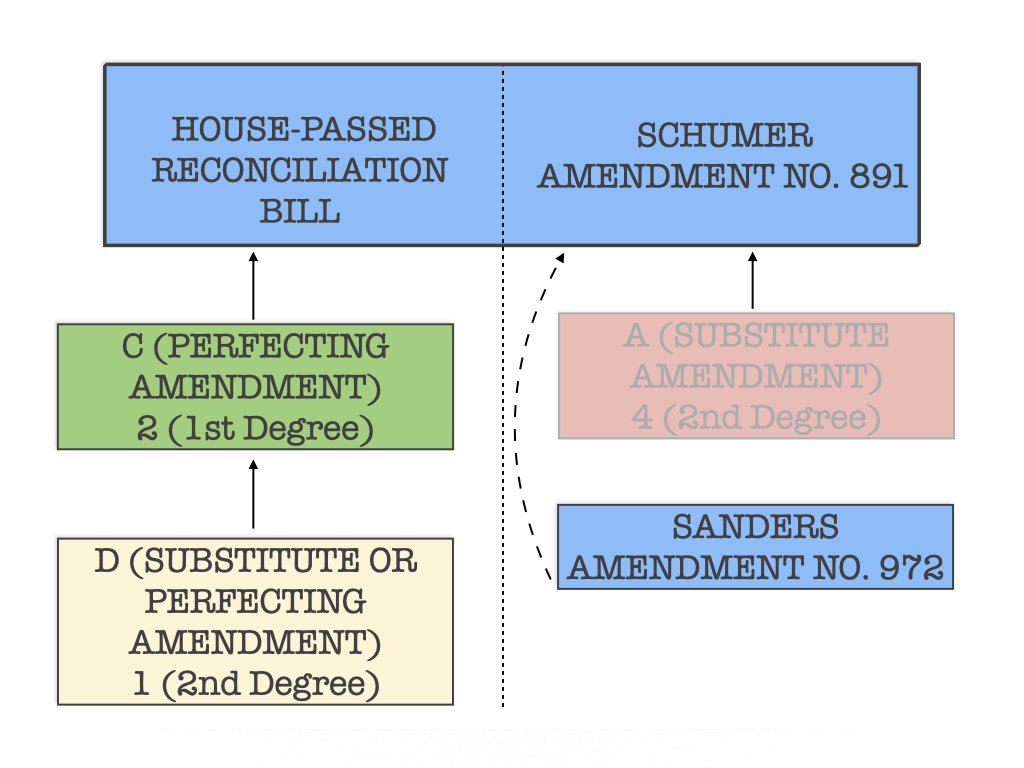

Schumer’s amendment, once pending, had the effect of putting the Senate on its third amendment tree (or chart 3 in Riddick’s Senate Procedure). The amendment trees depict the number and type of amendments senators may offer to a bill (or other amendments already pending) on the Senate floor.

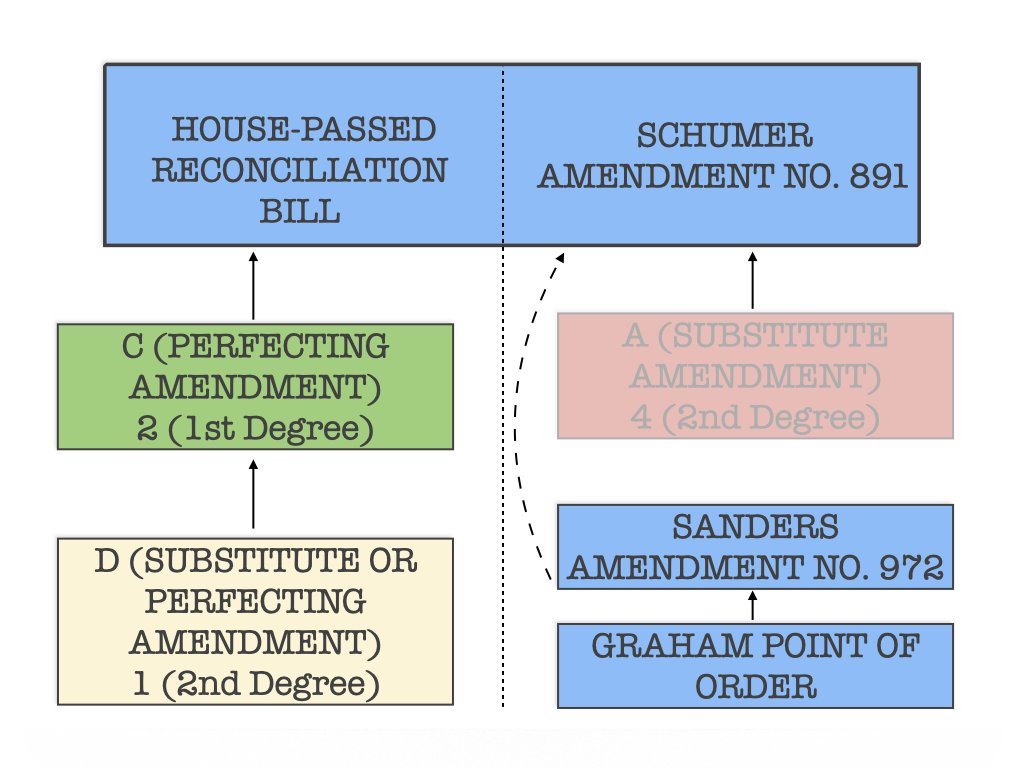

The Senate was in the following posture after Sanders offered his amendment to the Schumer amendment:

Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., then raised a point of order against the Sanders amendment because it violated the Byrd Rule's "merely incidental" test.

The Senate rejected Sanders’ bid to waive the Byrd Rule/Graham’s point of order and permit an up-or-down vote on his amendment by a 42 to 58 vote. By trying to add the minimum wage provision to Schumer's amendment instead of keeping it in the underlying House-passed bill, Sanders created a parliamentary situation in which the Senate could easily set a new precedent that the minimum wage provision violated the Byrd Rule's "merely incidental" test. Sanders also created a parliamentary situation that allowed seven Democrats to vote against increasing the minimum wage while supporting it publicly on the grounds that the reconciliation rules did not permit them to include it in the underlying reconciliation bill when those rules were, at best silent, on the question.

Democrats Set Themselves Up To Fail

Democrats set themselves up to fail in the Senate even though the House-passed reconciliation bill included a minimum wage provision. Democrats committed their first strategic error when the Senate’s presiding officer - a Democrat – chose to ignore the absence of precedent and decided not to declare Graham's point of order invalid. This decision forced Sanders to try waiving the Byrd Rule – which requires sixty votes – and, in the process, lead the Senate to set a precedent that Graham's point of order was valid. Ruling Graham's point of order invalid would have disadvantaged opponents of the minimum wage provision instead by forcing them to get sixty votes – not Sanders – to overturn the presiding officer's ruling.

Second, the House’s decision to locate the minimum wage provision in Title II of the reconciliation bill instead of at its end made it practically impossible under the Senate’s rules and precedents for Sanders to force a clear up-or-down vote on the minimum wage provision that did not trigger a point of order.

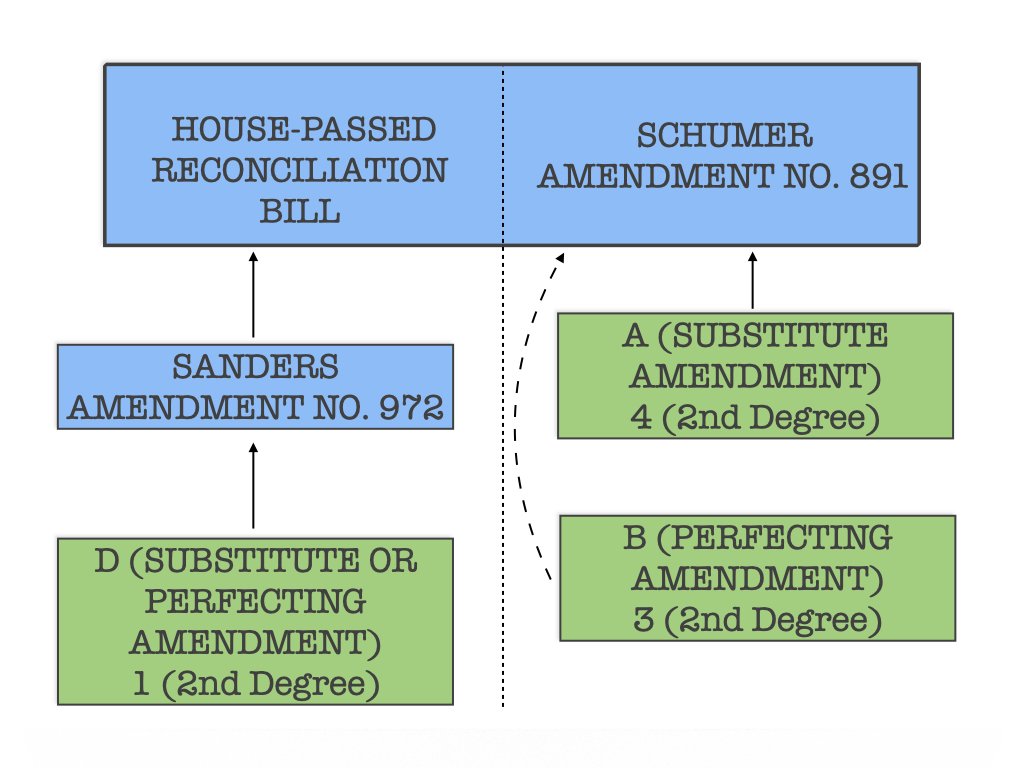

Setting up a clear-up-or-down vote on the minimum wage question that did not trigger a point of order required Sanders to offer an amendment to the underlying House-passed bill that included everything Schumer's amendment had but did not also remove the minimum wage provision.

Sanders’ amendment in this scenario would not have been subject to Graham’s Byrd Rule point of order because it would not include a minimum wage provision.

Sanders’ amendment would instead strike all after the first word until the minimum wage provision and insert the substantive text of Schumer’s amendment. This maneuver would have forced Senators to decide between leaving the minimum wage provision in the underlying bill and removing the minimum wage provision from the underlying bill. The Sanders and Schumer amendments would be identical in all other aspects.

House Democrats precluded Sanders from employing this maneuver when they included the minimum wage increase in Title II of their reconciliation bill instead of at its end. This is because the Senate's precedents prohibit amendments that touch a bill in more than one place. Consequently, Sanders could not in a single amendment change the House-passed bill before the minimum wage provision in Title II and after it without also changing the provision itself. And Sanders’ amendment would be subject to a Byrd Rule Point of order if he preserved the minimum wage provision by adding it back into the House-passed bill.

The Take-Away

Outcomes in Congress are never independent of the process by which they are chosen. Lawmakers may use the rules that govern the legislative process to advantage their preferred outcomes. By extension, lawmakers may, when needed, alter the range of possible outcomes by changing the process. This logic applies to all lawmakers, regardless of whether they are in the majority party or the minority party, or if they constitute only a minority of the majority party. The fact of being outnumbered numerically thus does not necessarily prevent lawmakers from winning in a legislative debate.

If Democrats had not made these strategic errors, Sanders could have forced senators to vote on the minimum wage provision and proponents of that provision could have worked to make it difficult for them to vote no. Democrats in the House and Senate can therefore increase the likelihood that Congress expands LPR via reconciliation if they are willing to learn from their mistakes in the minimum wage debate.